Controlling Your Breath Is an Easy Way to Improve Mental and Physical Health

By Sumathi Reddy

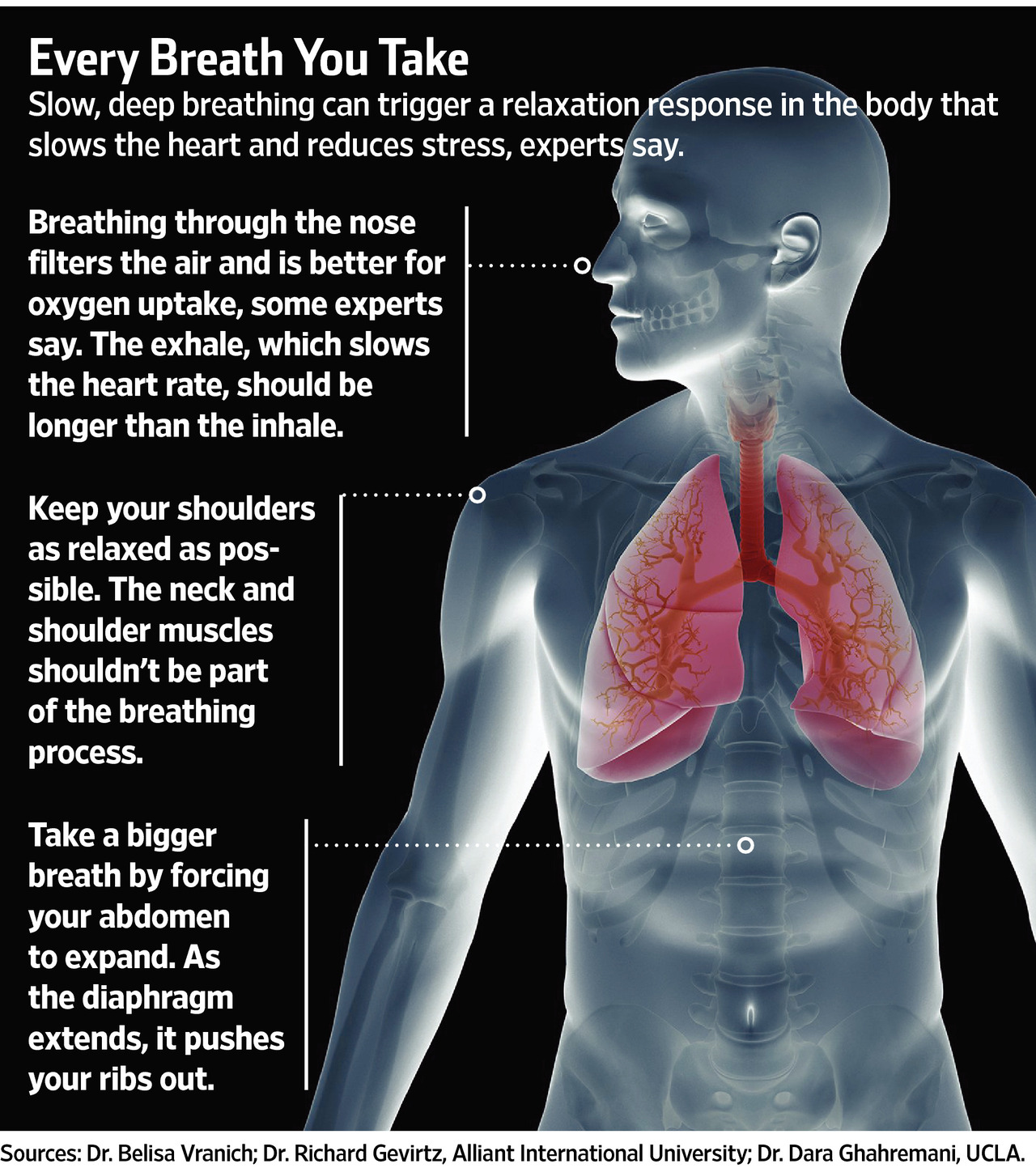

Slow, deep and consistent breathing has been shown to have benefits in treating conditions ranging from migraines and irritable bowel syndrome to anxiety disorders and pain. PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES

Take a deep breath and relax.

Behind that common piece of advice is a complex series of physiological processes that calm the body, slow the heart and help control pain.

Breathing and controlling your breath is one of the easiest ways to improve mental and physical health, doctors and psychologists say. Slow, deep and consistent breathing has been shown to have benefits in treating conditions ranging from migraines and irritable bowel syndrome to anxiety disorders and pain.

“If you train yourself to breathe a little bit slower it can have long-term health benefits,” said Murali Doraiswamy, a professor of psychiatry at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C. Deep breathing activates a relaxation response, he said, “potentially decreasing inflammation, improving heart health, boosting your immune system and maybe even improving longevity,”

To help foster the habit of healthful breathing, a San Francisco technology startup recently launched a wearable device called Spire that tracks breathing patterns and tells users when they are too tense or anxious. “One of the goals of this work was, ‘How do you make it so simple to shift into calm or focus that people don’t have to stop what they’re doing?’” said Neema Moraveji, co-founder of Spire and director of the Calming Technology Lab at Stanford University.

Many early buyers of the $150 Spire are office workers who spend a lot of time on computers. Research has found people working on computers often hold their breath, an action referred to as screen apnea, he said.

Belisa Vranich, a New York City-based clinical psychologist, has been conducting breathing workshops around the country for just over a year. Among her biggest clients: corporate managers eager to learn how to better manage stress.

Dr. Vranich says she instructs clients to breathe with their abdomen. On the inhale, this encourages the diaphragm to flatten out and the ribs to flare out. Most of us by instinct breathe vertically, using our chest, shoulders and neck, she says.

Abdominal, or diaphragmatic, breathing is often taught in yoga and meditation classes. Experts say air should be breathed in through the nose, and the exhale should be longer than the inhale. Dr. Vranich recommends trying to breathe this way all the time but other experts say it is enough to use the technique during stressful or tense times or when it is necessary to focus or concentrate.

Slow breathing stimulates the vagus nerve, which runs from the stem of the brain to the abdomen. It is part of the parasympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the body’s “rest and digest” activities. (By contrast, the sympathetic nervous system regulates many of our “fight or flight” responses.)

The vagus-nerve activity causes the heart rate to decrease as we exhale, said Richard Gevirtz, a psychology professor at Alliant International University in San Diego. Vagal activity can be activated when breathing at about five to seven breaths a minute, said Dr. Gevirtz, compared with average breathing rates of about 12 to 18 breaths a minute.

The vagus nerve’s response includes the release of different chemicals, including acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that acts as an anti-inflammatory and slows down digestion and the heart rate, said Stephen Silberstein, director of the Jefferson Headache Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia who is working on an article on the vagus nerve and its functions.

GETTY IMAGES

When medical conditions are severe, such as with epilepsy, medical devices are sometimes implanted to stimulate the vagus nerve. For most people, slow, steady breathing is a natural way to stimulate the nerve.

Certain conditions, including asthma and panic disorders, have been shown to benefit from a different breathing technique—taking shallow breaths through the nose at a regular rhythmic speed of eight to 13 breaths a minute. For these patients, already anxious about their symptoms, deep breathing can cause them to take in too much air and hyperventilate.

Heart-rate-variability biofeedback uses breathing to train people to increase the variation in their heart rate, or the interval between heartbeats. The technique has been shown to have benefits for conditions including anxiety disorders and asthma. Biofeedback also makes breathing more efficient, said Paul Lehrer, a clinical psychologist at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, part of Rutgers University in New Jersey. On average most people reach this balance when breathing 11 seconds per breath.

Spire, the device that tracks individual breathing patterns, is a pedometer-like device that can be clipped onto pants or a bra strap and can sense breathing patterns without touching the skin. A sensor detects subtle torso expansions and contractions, said Stanford’s Dr. Moraveji. The device identifies people’s baseline breathing patterns and can tell users when they are tense or may need to take a deep breath. It includes an app that guides people in breathing exercises as short as 30 seconds.

Dr. Moraveji’s research includes a 2011 Stanford study of 13 students that found subjects on average took 16.7 breaths a minute when they were doing normal computer work compared with 9.3 breaths a minute when they were relaxed, he said. The study was published in the proceedings of the annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology.

A follow-up study involving 14 subjects found that giving feedback of breathing patterns on a computer screen allowed the subjects to control their breathing without decreasing their performance on an analytical task, Dr. Moraveji said. “We proved that because the breath is so easily controllable, you don’t have to interrupt your task in order to regulate your nervous system,” he said. The study was presented at the ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in 2012.

Dr. Vranich, the breathing coach, believes teaching people to unlearn dysfunctional breathing habits requires practice and exercises. Her group classes cost $150 for a three-hour workshop and private classes range from $350 to $450.

On a recent afternoon, she held a private session in her Manhattan studio with Joe March, a 40-year-old New York City firefighter who said he wanted to improve his lung capacity and condition for Brazilian jujitsu, a form of martial arts he practices.

Dr. Vranich positions many of her clients upside down, to better exercise the diaphragm muscles. She assisted Mr. March into a shoulder stand against a wall as she monitored his breathing. “Inhale, relax, and see if you can expand right by your diaphragm,” she said. “Exhale, squeeze your ribs at the same time.”

Earl Winthrop, a 60-year-old partner of a Boston wealth-management firm, is another of Dr. Vranich’s clients. “When I was working on the computer, I wasn’t breathing properly,” said Mr. Winthrop, who now does tailored breathing exercises and short bouts of meditative breathing. “I’m much more aware now. I feel more focused. I can calm myself down,” he said.